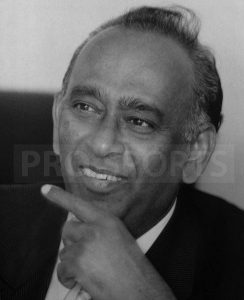

By

George Das: In Kuala Lumpur. Although his exceptional talent as a goalkeeper was already showing, he turned out as a striker for his alma mater in the under-18 team.

In fact he was spotted for his football flair as a 10 year-old forward by Master Francis Fernando of La Salle School Sentul at a primary inter-school match. He was then with a Chinese school.Fernando, who was the football teacher, saw his talent and requested his mother to transfer Chee Keong to La Salle Sentul.

Chee Keong honed his goalkeeping traits at La Salle Sentul under Master Fernando where Tony Francis also went to school with another schoolmate Christie Michael. Fernando, a dynamic sports teacher, will make Chee Keong play in goal and also as a centre-forward. He also trained him to be a sprinter and had the distinction of running just under 11 seconds in the 100 yards.

Christie Michael, who was Chee Keong’s teammate from La Salle School Sentul through to St John’s Institution, remembers this wonderful guy: “I was a left-winger. All I had to do was send the ball to Chee Keong, and he will put the finishing touches.”

“After he scores, without fail he’ll run up to me and hug me,” recalled Christie.

However in St. John’s, Chee Keong hardly played between the“posts” for at 15 years of age, he was already in the school’s 1964 under-18 team. He was equally good at dribbling and so coach Major Mok Wai Kin deployed him in the attack.

“He terrorised the opposing defence with his footwork and it was a delight to watch him,” recalled Joseph Teng, a teammate from the St. John’s senior team. At the same time he was already representing the Malaysian Youth team appearing for them at the tender age of 13 and winning accolades as a talented goalkeeper.

He was just not a one sport sensation. Turning out for St. John’s at inter-schools competitions, he also excelled in athletics (100, 200 & 400 yards), and rugby. He was a fast wing half in rugby.

“Chee Keong was a sports protégé with exceptional talent. Though he was an excellent goalkeeper, he could have excelled in any sport,” commented A. Vaithilingam, a former Malaysian Schools Sports Council secretary.

Making his debut for Malaysia in the 1965 Merdeka Football Tournament at 15 and the youngest Malaysian to do so, he was the reserve keeper to Teh Cheng Lee but the following year he became the first choice and continued to appear for the country until 1970. He played alongside M. Chandran, N. Thanabalan, Ghani Minhat, M. Kuppan, M. Karathu, Soh Chin Aun, Santokh Singh, the Choe brothers Robert and Richard, and many others before turning professional in Hong Kong.

“I met him in 1963 when he was a reserve in the Selangor Malaysia Cup team and just a schoolboy,” was Chandran’s recollection.

He continued: “A very reliable keeper. We could play with confidence with him in goal and we could rely on him to be in control in any situation in the penalty area. He was good at diving for the ball from any position and also good in the air. He was no doubt the best goalkeeper we have ever had.”

Thanabalan, had some great moments with Chee Keong whom he described as “full of fun” and as one who was always playing pranks and jokes on the senior players but on the field he was a much disciplined person.

He told how opposing forwards were scared of going up into the air with Chee Keong.

“Great forwards like Indonesia’s Sujipto, Jacob Sihasali and Singaporeans Quah Kim Swee and Majid Ariff wouldn’t dare tangle with him lest they get hurt,” Thanabalan quipped.

At the 2017 Sports Flame function, where former sports personalities came together, Chee Keong and Thanabalan were overheard to sharing a joke about a two touch football.

“He kicked the ball into the opponents half. It bounced over the centre back and rolled towards goal. Before the opposing keeper could get to it, I pounced on it and scored. So we called it a two touch football.”

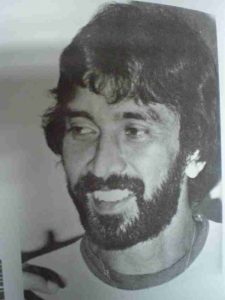

Arriving in Hong Kong in late 1970, Chee Keong became an overnight celebrity, a “football rock star.”

A black-belt karate exponent, he had the looks of something between Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, and the fans revered this brilliant goalkeeper.

He was dubbed “Crazy Sword” and “Asian Steel Gate.” He was getting paid more than any other player in the Hong Kong league.

So popular was he that in one match where he appeared for South China FC in the mid-70s, he was flown into the middle of the Hong Kong Stadium which was filled to the brim with 20,000 spectators in a helicopter.

Tickets were sold out for almost all matches he played during his stint with Rangers, South China, Tung Shin, Jardines and Caroliners from 1970 till 1982.

Chee Keong set the trend for many Malaysians turning professional in the Hong Kong league…Khoo Luen Khen, Chan Yong Chong, Wong Kam Fook, Chan

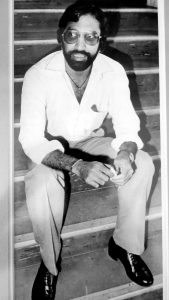

We had just entered the traditional Chinese dhobi shop at Number 6, Ipoh Road in Kuala Lumpur, and waiting for us inside was a cheerful Chow Chee Keong.

A pile of clothes all ironed and folded was stacked behind where he was sitting. It was a day in June 1973, when he had just returned to his parents’ home during the off-season of the Hong Kong pro football league.

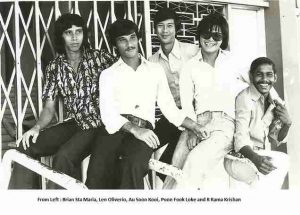

I was then with the STAR and was tagging along with Tony Francis of New Straits Times to interview the international star keeper who was making waves in Hong Kong as a professional player. These visits to interview Chee Keong will continue throughout the 70s for me.

Chee Keong was two years our junior at St. John’s Institution in Kuala Lumpur. Although his exceptional talent as a goalkeeper was already showing, he turned out as a striker for his alma mater in the under-18 team.

In fact he was spotted for his football flair as a 10 year-old forward by Master Francis Fernando of La Salle School Sentul at a primary inter-school match. He was then with a Chinese school.Fernando, who was the football teacher, saw his talent and requested his mother to transfer Chee Keong to La Salle Sentul.

Chee Keong honed his goalkeeping traits at La Salle Sentul under Master Fernando where Tony Francis also went to school with another schoolmate Christie Michael. Fernando, a dynamic sports teacher, will make Chee Keong play in goal and also as a centre-forward. He also trained him to be a sprinter and had the distinction of running just under 11 seconds in the 100 yards.

Christie Michael, who was Chee Keong’s teammate from La Salle School Sentul through to St John’s Institution, remembers this wonderful guy: “I was a left-winger. All I had to do was send the ball to Chee Keong, and he will put the finishing touches.”

“After he scores, without fail he’ll run up to me and hug me,” recalled Christie.

However in St. John’s, Chee Keong hardly played between the“posts” for at 15 years of age, he was already in the school’s 1964 under-18 team. He was equally good at dribbling and so coach Major Mok Wai Kin deployed him in the attack.

“He terrorised the opposing defence with his footwork and it was a delight to watch him,” recalled Joseph Teng, a teammate from the St. John’s senior team. At the same time he was already representing the Malaysian Youth team appearing for them at the tender age of 13 and winning accolades as a talented goalkeeper.

He was just not a one sport sensation. Turning out for St. John’s at inter-schools competitions, he also excelled in athletics (100, 200 & 400 yards), and rugby. He was a fast wing half in rugby.

“Chee Keong was a sports protégé with exceptional talent. Though he was an excellent goalkeeper, he could have excelled in any sport,” commented A. Vaithilingam, a former Malaysian Schools Sports Council secretary.

Making his debut for Malaysia in the 1965 Merdeka Football Tournament at 15 and the youngest Malaysian to do so, he was the reserve keeper to Teh Cheng Lee but the following year he became the first choice and continued to appear for the country until 1970. He played alongside M. Chandran, N. Thanabalan, Ghani Minhat, M. Kuppan, M. Karathu, Soh Chin Aun, Santokh Singh, the Choe brothers Robert and Richard, and many others before turning professional in Hong Kong.

“I met him in 1963 when he was a reserve in the Selangor Malaysia Cup team and just a schoolboy,” was Chandran’s recollection.

He continued: “A very reliable keeper. We could play with confidence with him in goal and we could rely on him to be in control at any situation in the penalty area.He was good at diving for the ball from any position and also good in the air. He was no doubt the best goalkeeper we have ever had.”

Thanabalan, had some great moments with Chee Keong whom he describes as “full of fun” and as one who is always playing pranks and jokes on the senior players but on the field he was a much disciplined person. He told how opposing forwards were scared of going up into the air with Chee Keong.

“Great forwards like Indonesia’s Sujipto, Jacob Sihasali and Singaporeans Quah Kim Swee and Majid Ariff wouldn’t dare tangle with him lest they get hurt, Thanabalan quipped.

At the 2017 Sports Flame function, where former sports personalities came together, Chee Keong and Thanabalan were overheard to share a joke about a two touch football:” He kicked the ball into the opponents half. It bounced over the centre back and rolled towards goal. Before the opposing keeper could get to it, I pounced on it and scored.So we callit a two touch football.”

Arriving in Hong Kong in late 1970, Chee Keong became an overnight celebrity, a kind off “football rock star.”A black-belt karate exponent, he had the looks of something between Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, and the fans revered this brilliant goalkeeper.He was dubbed “Crazy Sword” and “Asian Steel Gate.” He was getting paidmore than any other player in the Hong Kong league.

So popular was he that in one match where he appeared for South China FC in the mid-70s, hewas flown into the middle of the Hong Kong Stadium which was filled to the brim with 20,000 spectators in a helicopter.

All matches he played for the various clubs from 1970 till 1982… Rangers, South China, Tung Shin, Jardines, and Caroliners match tickets would be sold out and it would leave largenumbers of fans ticketless and disappointed.

Chee Keong set the trend for many Malaysians turning professional in the Hong Kong league. ..Khoo Luen Khen, Chan Yong Chong, Wong Kam Fook, Chan Kok Leong, Fung Seng Meng, Yee Seng Choy, Lim Fung Kee, Wong Voon Leung, Lee Ah Kau, Yip Chee Keong and for a brief spell even Wong Choon Wah and Soh Chin Aun.

For Lim Fung Kee, his memories go back to when he was a 13 – year-old student of Cochrane Road School and Chee Keong was 16.He watched him play in a Selangor League match: “He became my idol and inspired me to be a goalkeeper. I admired him,” said Fung Kee, who played for Malaysia in the 1972 Munich Olympic Games.

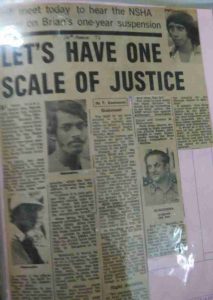

He never gave up playing for the Malaysian national team. He made a brief comeback for the 1981 Asian Cup in Kuwait… a comeback he was utterly disappointed till his death. Malaysia fared terribly and it was dubbed the “Kuwait Debacle.”

I remember him telling me that it was a nightmare. There was bitterness when he said: “There was only one reason why we fared so badly. The team that played in Kuwait was never the one that the public was led to believe.

“There never was a team. Individual talent there was but if you think that all these made up a team, in the real sense of the word, you are badly mistaken.

According to Chee Keong the single biggest flaw in the team was “factionalism”, one born out of coach Karl Weigang’s error in playing favourites.” This was obvious right from the start of centralised training and it was allowed to fester in Kuwait. Weigang’s favourites were allowed to dictate everything, the pattern of play and even down to the final choice of players to be fielded.”

But apart from this only disappointment, Chee Keong’s nearly 18-year chequered football career had many memorable moments which overwhelm that final fling with the national team. He loved to talk about the few encounters he had facing Pele and his Santos team from Brazil. Pele found many a time he had difficulty penetrating the “Asian Steel Gate” Chee Keong.

And there was the time in 1972 when he faced the diminutive Brazilian forward Tostao and Cruzeiro. He thwarted Tostao from scoring a number of times in this encounter. After that match, Cruzeiro offered to sign him up and even get him a Brazilian citizenship.But Chee Keong declined the offer and told me that he will never give up being a Malaysian.

After his football career ended in 1982, he returned to Malaysia and took up golf. V. Nellan, one of Malaysia’s veteran pro golfers, recalled the day Chee Keong went to him for some lessons at the Seremban International Golf Club. “Among all the other sportsmen who had taken up this game, Chee Keong was the most talented. He had a knack for the game. I just had to show him once or twice, and he quickly picked it up,” Nellan recollected. “He would always talk to me about how to keep fit and food. Keep away from oily food,” he would say.

He quickly picked up the game and became a professional golfer in 1984. He played on the Malaysian pro circuit for a couple of years and returned to Hong Kong where he became very popular among the golfers. He turned to teaching golf in Hong Kong and continued giving golf lessons in Malaysia on his return.

Chee Keong’s dream was to start a special “School for Goalkeepers” in Malaysia. He wanted to impart all his knowledge in this department to the younger generation of Malaysians. He had the credentials, having been voted Asia’s Best Keeper for five consecutive years from 1966-1970.

“Without this breed of courageous, dedicated and talented men, no team can survive, however impregnable their defence may be, particularly at the higher levels of international football,” he wrote for his column in Sports Mirror.

He believed in discipline, competitiveness, self-confidence, commitment, determination and emotional maturity in becoming a really good goalkeeper.

Sadly the school never materialised, but I have been most fortunate to have journeyed with this humble person and the only legacy of him I possess are some photos and 15 columns of “CHEE KEONG’S GOAL TIPS”.

By

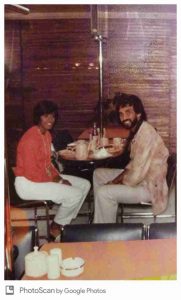

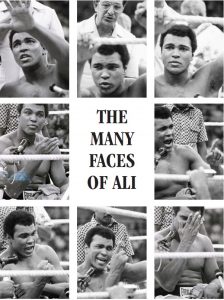

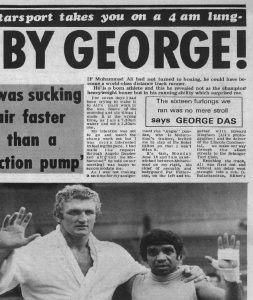

By Many recordings of Ali are out there in the market but I suspect this is probably the only recording which has the three-time heavyweight boxing champion reciting poems.I was most fortunate to be there alone with him in the presidential suite of the Kuala Lumpur Hilton. Dawn had just broken on the Thursday of June 26th, 1975 and the No. 1 country song at that time was Don Williams’ “You’re my best Friend”.

Many recordings of Ali are out there in the market but I suspect this is probably the only recording which has the three-time heavyweight boxing champion reciting poems.I was most fortunate to be there alone with him in the presidential suite of the Kuala Lumpur Hilton. Dawn had just broken on the Thursday of June 26th, 1975 and the No. 1 country song at that time was Don Williams’ “You’re my best Friend”.

Beautiful people don’t just happen. The most beautiful people we have known are those who have known defeat, known suffering, known struggle, known loss, and have found their way out of the depths.

Beautiful people don’t just happen. The most beautiful people we have known are those who have known defeat, known suffering, known struggle, known loss, and have found their way out of the depths.

If you have an interesting personal story of a sports personality with photographs and video, we would like to publish it on this site.

If you have an interesting personal story of a sports personality with photographs and video, we would like to publish it on this site.