THE LYDIA CRAZE

By R VELU

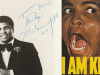

The Marina-mania that gripped the athletics scene in the 1977 SEA Games is a thing of the past. It’s now the Lydia craze. Everywhere you go in Manila, people will go into rhapsodies over this long-legged darling of the track.

Lydia De Vega has been described as having world class promise. And she is set to take over as the new SEA Games queen of the track from Burmese star Than Than. What’s her background? How did she develop her athletic ability? And what does she think of her future? Sports Mirror finds out.

“I want to be world champion,’ said Lydia, standing tiptoe and raising her right hand…. reaching for the sky. “And I want to be an Olympic champion,” she added opening her eyes wide.

“Well” I said, “If you are going to be a world champion, you’ll definitely be an Olympic champion.”

“Not necessarily,” she quickly countered, breaking into a wide grin.

“There have been world champions before who didn’t win any Olympic gold,” she had me there. How many Ron Clarkes, Jim Ryuns…. world record holders had retired without an Olympic gold to their name.

This observation comes from a 17-year-old college student who bursts into girlish giggles at the slightest joke, who’s all arms and movement when trying to describe something vividly, has a simplicity that’s disarming and a charm that’s appealing, rolls her R’s and ‘aahhs’ her A’s with the usual Filipina accent.

Fame hasn’t changed her, say many Filipinos. She is still the simple bright-eyed girl from Barrio Kalbaryo, a thickly populated and poor suburb of metro-Manila, a suburb of closely connected houses muddy pathways where costume jewellery is made and sold.

She’s the girl who developed her running ability by sprinting more than 500 metres to buy cigarettes for her father when she was very young. A girl who used to play ‘Chinese Garter” – a popular street game where a tape or string of rubber band is held up high by two kids and the third takes a flying kick hooks the string down with the right and whips over without the leg touching the string – with such grace and balance that those who saw her said she was a natural.

TEMPTATION

It was the game she was playing when we met the other day at the 5,000ft high Gintong Alay athletics training camp in Baguio City. She had finished training in the morning and was dressed casually – light-brown slacks and a yellow T-shirt that had ‘Halloween’ printed boldly in front.

The heptathlon trails were going on and for Lydia, the finishing tape strung between the posts presented a temptation she couldn’t resist. ‘Chinese Garter’. This time she sailed over it straddle style without touching the tape.

Screams of delight and laughter greeted her each time she attempted the jump. And Lydia would respond by pulling funny faces. Watching her, you would hardly guess that this is the girl who is being described as future world class material. She is the uncut diamond in a glittering pile of talented athletes that the Filipinos have brought together.

“Do you know I would play the game to this height even when I was very young,” she said stretching her right hand well above her head and laughed.

What was that? A glitter of silver? A wire hooked to one tooth? False teeth, I reasoned.

“You have false teeth,” I asked, surprised because she seemed to have such a beautiful set. Surprised because she was young and healthy.

“Yes” she cried delightedly with impish humour at my surprise. She lost her front four upper teeth when very young. “Too many sweets and candies. I still like them. I like eating very much, that’s why I’m so fat,” she spread her arms sideways descriptively and wiggled her hips.

Lydia was still running gap-toothed in last year’s national championship. It was only late last year that she received her dentures from her father Francisco, her one-time coach who is now her confidante and masseur.

Just then he came up, right hand in a bandage, and smiled widely. His front four teeth were also missing. “I lost them in a fight,” he explained. He was a boxer in his younger days.

It was in the streets and alleys of Kalbaryo that Lydia developed her talents. When she was just nine, she would run like a hare to buy cigarettes for her father.

It was while playing ‘Chinese Garter’ that Lydia was spotted. When school was over it was the streets and ‘Chinese Garter’ for most of the girls. One school teacher noticed the facile grace and perfect balance with which she executed her jumps.

He asked Lydia to compete in the school sports the following day. She was then just a frail, waif-like 12-year-old. Lydia agreed. But she had to win over her skeptical parents first and that was left to a neighbour who persuaded her parents to let her compete.

Grudgingly, Francisco forked the pesos necessary to buy a new pair of shorts for Lydia. But unconvinced, Francisco did not attend the meet. The only fan Lydia had then was her neighbour who was cheering wildly as Lydia stormed to first place in five events.

Some dust was stirred as an athlete couldn’t compete in more than four events. But Lydia was given her prizes all the same. That finally convinced Francisco that his daughter had some talent after all. He began attending her sports meets and became her first coach and trainer.

Simple, soft-spoken, chain-smoking Francisco has been a controversial figure in Lydia’s athletics career. There is this story of how he slapped Lydia in public when she was training at the Marikina Stadium where she set the national 400 record of 54.6 last year.

Lydia made several foul jumps in the long jump. Francisco, convinced that she was fooling around, gave his daughter two tight slaps in front of the other athletes.

Lydia cried softly …. “It hurt,” she said the other day, rubbing her cheeks. But it worked, and Lydia was more serious and went 5.5-plus metres in her subsequent attempts.

“I have these two hands,” said Francisco, the boxer in him surfacing. “If the right is not enough, then I give the left. But I don’t ill-treat my children. I give them what they want. When Lydia had washed up and was ready to go back that day when I slapped her, she came up to me smiling and asked, ‘Papa. Give me some money.’ I gave her the money. I only discipline my children. Francisco has six children, three boys and three girls. Lydia is the fourth.

There was another incident when an angry Francisco pulled his daughter out from training camp in Baguio because she was being put into the 800 metres. Many coaches, including Asia’s legendary Chi Cheng, believe that it is over the 800 metres that Lydia will make her mark.

Those long legs were meant for the 800 metres, they said. But Francisco would have none of it. She is too young for it now. Maybe when she is older, he said. Attempts to get Lydia back into camp failed and she was suspended for some time last year before the warring parties were reconciled.

Father and daughter enjoy a very close relationship. “He has every right to spank me and decide what’s good for me,” said Lydia. Then a ring on her engagement finger caught my eye.

Is she engaged? “Yes to my father,” she joked. “He made it himself and gave it to me. I wear it always.” Francisco is also an artisan who makes the costume jewellery that one finds in tourist centres in Manila.

PROMINENCE

It was as a spindly-legged schoolgirl that Lydia swept into prominence by bagging three individual golds and two relay golds at the 1979 Singapore Asean Schools athletics championship. Now Lydia, who turns 16 on December 26th – Boxing Day – has grown in stature and physique.

“I am 5ft 6ins now,” she proclaims proudly, “and weigh 120lbs.” Again, that hip wiggle. “I am a first-year student in college and hope to pass out with a degree in physical education.”

Lydia renews her rivalry with Malaysia’s Mumtaz Jaafar – a rivalry which dates backs to the Singapore Asean Schools meet – in this Manila Sea Games and will attempt to crack the myth of invincibility surrounding Burma’s Than Than who holds the Sea Games 200m, 400m, 800m and 400m hurdles records.

The brown-skinned, dark-eyed Filipina is down for the 200m and 400m where she has a season’s best of 24.0 and 55.2 …. Which make her the brightest gold medal prospect in both events.

Can she win the events? The playful child in Lydia took a backseat. She looked mournfully at her left instep. Her left foot was bandaged. “I really don’t know,” she shook her head. “I injured my foot, you know when I was climbing the stairs back to camp after training in Baguio.

“It’s a bit better now. But I can only hope to do my best. I hear that Mumtaz has done some good times. And Than Than is a very powerful and experienced runner. I can try my best.”

Lydia has been taking it easy during training feeling secure that the two golds are hers, says Gintong Alay head coach Tony Benson. But when she heard that Mumtaz had gone under 12 for the 100m and clocked 24.4 for the 200m, she saw the threat and put in more effort.

Benson agrees that Lydia has world class potential. “She will make a very good 800m runner. She has the speed but will have to build up stamina and endurance and put in more effort,” he says.

Lydia could make an impact in next year’s New Delhi Asian Games. But it is the 1988 Olympics that every athletics follower in The Philippines is waiting for. This is where she is going to make her name known worldwide, they say.

“That’s if some boy doesn’t come along by then and asks her to decide between him and track and field,” quips Nars Padilla, camp commandant at Baguio City, who says that Lydia is a very exemplary athlete.

NOTE: This story appeared in the weekly Sports Mirror (Malaysia) in December 1981 before Lydia de Vega became a “star”.

If you have an interesting personal story of a sports personality with photographs and video, we would like to publish it on this site.

If you have an interesting personal story of a sports personality with photographs and video, we would like to publish it on this site.