By

By

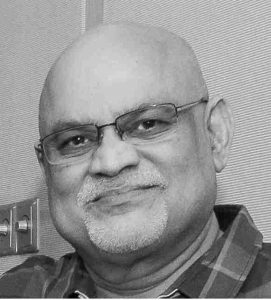

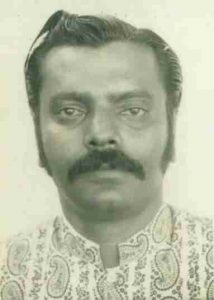

Lazarus Rokk: My first ambition in life, since my upper secondary days in St John’s Institution, has always been to be a lawyer, a litigating lawyer fighting courtroom battles,as arguing is what I do best. I suppose that’s an ability which comes with my ethnicity. It’s in our DNA. Which is probably why litigation reads well with Indian lawyers.

But, as it turned out, I couldn’t get a place at the University of Malaya after my HSC, and there weren’t a myriad of universities and colleges at my disposal back then, not to mention I wasn’t born with a silver spoon in my mouth. So, grudgingly I was forced to abandon that ship until such time when I could afford to pay my way through law school in England.

An opportunity arose in early 1975 at The Star, at its office at 7, Jalan Travers. The fledgling newspaper that was just four years old then, needed a feature writer. I had just turned 20 a month ago, and had found myself in an office that was situated a floor above Hawaii Bar, a girlie bar – not my kind cos they looked like aunties, but nevertheless they were a favourite with the production boys.

And little did I expect that journalism, a profession that I had stumbled into, merely to serve a bigger purpose – law school – was to change everything I felt and loved. I was so seduced by its charm, power and glamour that suddenly cross-examinations and courtroom battles, didn’t seem enticing enough anymore.

The allure of journalism was just so overwhelming for a 20-year-old who was coming out in the world for the first time from a regimented lifestyle, imposed so religiously and enforced by my school teacher dad, that even prison wardens would look like social workers.

Like an unleashed horse freed from its prison, I bolted into the ‘wilderness’ tasting and savouring the freedom, the power, and the thrill of seeing my byline in the newspaper. At that time, even though The Star’s circulation couldn’t have been more than 30,000 copies, I would be scrambling, like an excited teenager on his first hot date, for the papers the next day to look for my story with the byline. That thrill never lost its oomph, even till the day I quit in 2006.

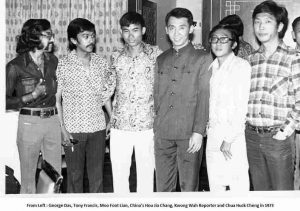

But George Das, my first mentor at The Star, always watched over me and didn’t let me wander too far into that wilderness. He always kept me within his sights, showing me the ropes, and even introducing me to sportswriting by getting me to contribute to the paper’s magazine Fanfare. I used to write weekly profile stories on sports personalities. And that launched me into sportswriting.

But George Das, my first mentor at The Star, always watched over me and didn’t let me wander too far into that wilderness. He always kept me within his sights, showing me the ropes, and even introducing me to sportswriting by getting me to contribute to the paper’s magazine Fanfare. I used to write weekly profile stories on sports personalities. And that launched me into sportswriting.

The thing that I loved about this job, which was really a joy, was that while we worked hard, we also played hard. And it was on one of those ‘play hard’ nights that I met Fauzi Omar of Malay Mail back then. It was at the Glass Bubble disco (Uncle Chilis now) at Jaya Puri Hotel (PJ Hilton now). It was where the sportswriters from The Star, NST, and Malay Mail hung out, our final pit stop of the night. Fauzi and I were the only rookies in that motley crew of hardened sports journalists, but we were made to feel at home with them. Before the night was over, which was like about 4am, Fauzi and I had forged such a friendship that it was to grow in strength and last to this day, 43 years later. George, dear George, never touched a drop of alcohol, nor lit up a cigarette in his entire life, but he will be there among all of us every night we were out. And “By George!’ it would be this little guy who will be dancing on table tops in pubs, drunk only on orange juice.

You know, when I keep looking back at the proceedings of my life as a journalist, I am convinced that it was journalism and its life lessons that have defined my character, and who I am today. I don’t know how many of you can boast of a career or a profession that has shaped the way you are, the way you feel, and the way you think. But mine did.

My first encounter with life’s lessons was in early 1976. In one of my usual mornings at work, I checked in with my features editor, Maureen Hoo, to discuss an angle for a feature story. But that day was different. On that day, she handed me an envelope, which I eagerly opened, believing it to be a promotion letter. To my utter shock and disbelief, it was my letter of termination. I looked up at Maureen, and I knew she had nothing to do with it. She looked sad, and was struggling for a sensible explanation.

I was 21, impressionable, governed mainly by my emotions, and ready to fire from my hips at a twitch of an eye. I was so blinded by rage that I couldn’t see through the web of deceit. It was George, who pointed out to me that something was amiss because my letter of termination was signed by the Director of Finance, and not legally the Managing Editor, who happened to be abroad then.

I was 20, and naïve as an uninitiated 20-year-old could get, to office politics. I couldn’t believe I was a victim of a conspiracy. I couldn’t believe it, as I was just a cadet journalist, and I would have thought I didn’t pose a threat to the powers that be. But as it turned out, I had stepped on a few sensitive toes belonging to news editors whom I had unwittingly embarrassed with my one-liners, that can sometimes be offensive to people with fragile egos, and critically deficient in a sense of humour.

A reliable source, who was in a position to listen in on telephone conversations, told me confidentially that these humourless people, who had the ear of the top-level management, had falsely accused me of starting a union. A union then, was perceived as an abomination, something to abhor as it was made out to be an organisation of trouble makers. But in reality, all I was trying to do, given my passion, was to help put together a sports club.

That was my first cut, and somehow it didn’t seem to feel deeper than the one dealt by my first love, just a year ago when I was in Upper Six. For, on the day I had received the letter, there was a house party organised by a former colleague, and I found myself there together with George, Fauzi, music man Patrick Teoh, and lawyer Sivarasa, who’s now a PKR man. In the middle of the night, when we were in high spirits, in more ways than one, I told Fauzi very nonchalantly that I had lost my job. At first Fauzi was stunned into silence, not knowing how to react. But when I laughed, he thought I was crazy, and he too laughed along.

But to use a very well-worn phrase, all that’s water under the bridge now. As I picked myself up, and brushed the arrows off my back, I believed that even though life had dealt me an unkind hand in my first ‘round’, the deck was still fresh. And true enough, three months later, Fauzi informed me that he had spoken with Sunday Mail editor Ahmad Sebi, about a stringer’s (partime) job, for the sports pages. I was given a column to write, and it was called “Around the schools with Lazarus Rokk’. And that, kicked off my career as a full-fledged sportswriter.

At the risk of sounding banal, I felt like I was swept into a whirlwind romance with sportswriting.

I was so caught up in it, that I was working every day and enjoying every minute of it, working for both the Sunday Mail and the Malay Mail sports desk. Like Fauzi, George and I would always say, it wasn’t a job, it was fun. It got even better when I came on as a fulltime journalist in February 1978, assigned to the Malay Mail.

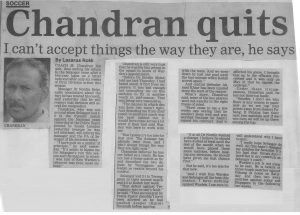

Things were just so hunky dory, until in January 1980, the management dropped the second bombshell in my career. I come back from my Christmas leave, looking forward to getting back into action again, when I get this transfer letter to the Johor Baru branch at Taman Maju Jaya, then. I looked in bewilderment at the letter, seeking a sensible explanation for this highly unprecedented decision for the Malay Mail.

Since I couldn’t make any sense of it, I decided to ask the boss man, Chuah Huck Cheng, the editor of the Malay Mail, what that was about. He said something about insubordination, and being a journalist who was taught to stand up for what’s right without fear or favour, I believed I would be given a chance to defend myself. I was mistaken. When Huck Cheng shouted “get the f..k out of my room”, I realised three things. One, when you are a rookie, you don’t have rights. Two, you never question your bosses, even though you mean well. And three, bosses don’t practise what they preach.

About that insubordination issue. Sometime in May 1979, I was given a show-cause letter, asking why disciplinary action shouldn’t be taken against me for not covering a Selangor Division 2 match, which at best would be worth a two-paragraph filler.

It so happened on that very evening, my sources told me that the Danish Thomas Cup team had arrived at the Subang Airport enroute to the Thomas Cup Finals in Jakarta, Indonesia. As a badminton beat reporter, it would naturally be incumbent upon me to follow this lead. Which I did. I managed to jump into their bus and followed them to the KL Hilton. I sat with their team manager Tom Bacher, whom I had met before through the late Punch Gunalan.

Bacher wanted to see the “sights of KL”. And being a good host, as we Malaysians are, I showed him around. To cut a long story short, when I got back to the office in Jalan Riong, it was almost 11pm. But I had tucked comfortably under my belt, and proudly too, five stories from my interviews with Bacher and some of his players. At the office, the sports editor, the late Maurice Khoo, and his deputy, the late Francis Emmanuel weren’t around. The Malay Mail editors and the sub-editors really start work at 5am every day, as we were an afternoon paper back then.

Nevertheless, my five stories filled up two and a half pages, with two page leads, and exclusives to boot. As a 24-year-old, still very wet behind the ears in journalism, I was naïve to expect a pat on the back the next day by the boss. But all I got was a bollocking for not covering that Div. 2 football match. They told me, the least I could have done was to make a call or two to get the results. Insubordination, was what it was, and I could offer no form of defence that would appease the big bosses.

Nevertheless, my five stories filled up two and a half pages, with two page leads, and exclusives to boot. As a 24-year-old, still very wet behind the ears in journalism, I was naïve to expect a pat on the back the next day by the boss. But all I got was a bollocking for not covering that Div. 2 football match. They told me, the least I could have done was to make a call or two to get the results. Insubordination, was what it was, and I could offer no form of defence that would appease the big bosses.

It was evident, that my outspokenness, my one-liners that were meant to be funny, and the self-confidence that I oozed effortlessly, were mistaken for arrogance, insolence, and effrontery. And they felt the need to put me in my place. But I wasn’t going to change for them. I was going to be whom I wanted to be and I was comfortable with that. Comfortable also with the knowledge that, this was just the beginning of tougher battles to come.

So, misunderstood, and lamenting my fate, I packed my bags and left home in OUG, Old Klang Road to JB. In the six-hour bus ride, I could only hear Francis who was sympathetic to my cause, telling me this: “Rokk, they are sending you to your graveyard.” With that sitting grimly at the back of my mind, I arrived at JB with a vengeance. I was angry, betrayed, torn away from my family, and totally disillusioned.

My first target was the Johor FA. The poor chaps, they didn’t know what hit them. I was on their backs for days, dismantling their administrative methods, and criticising everything that I could. Then one morning, the deputy president of the JFA, the late Datuk Suleiman Mohamed Noor, called my office and told me this; “Mr. Rokk, if you are truly interested in the welfare of Johor football, please come to my office tomorrow.”

Suleiman was also the state secretary then, and a very powerful man in the state government. His boss, the Menteri Besar, was Datuk Ajib Mohideen, the president of Johor FA, and the leader of Barisan Nasional’s invincible state. Those were enough credentials to intimidate a relatively rookie sportswriter.

Nevertheless I made my way to the imposing Sultan Ibrahim Building at Bukit Timbalan where the state government office was back then, with an open mind. I didn’t have anything to lose. I waited all of five minutes before I was ushered into his office. After the usual greetings, I sat myself opposite him waiting for the onslaught. To me it was a story-opportunity.

But there was no onslaught. He opened with: “Young man, the easiest thing to do in this world is to criticise people, and get paid for it.” I told myself true, but not enough. But that meeting changed my perspectives in journalism. The teachings in my formative years in the profession was to be impartial, to write it as we saw it. But after the two-hour chat with Suleiman, it became evident that to help the development of Johor sports, the media had to be inclusive. We had to be a part of the development process through our writing. And with that began my schooling in ‘development journalism’.

And as I told myself that Johor will be my graveyard only if I allowed it, I rounded up the gang in JB comprising Rizal Abdullah of The Star, Johari Mohamed of Berita Harian, Sudi Othman of Utusan Malaysia, and Kamel Osman of Bernama to set about the task. We formed a strong pact, and set about to provide the kind of media support that Johor sports needed to thrive on.

We ‘worked’ with the hardcore officials who were the unsung heroes in their respective sport. Among them, were teachers K. Sukumaran, coach of the 1982 Razak Cup football squad, and B. Rajakulasingam of SM Dato Jaafar who bred championship cricket players, and TNB’s Balbir Singh who was grooming hockey players.

These three coaches spent more time with their respective charges than with their own families. But their efforts and sacrifices weren’t in vain. Sukumaran’s boys grew into the senior ranks to take Johor to their first Malaysia Cup quarter-final in 1984, and then making history in 1985 by winning the Malaysia Cup. Rajakulasingam’s boys were the perennial winners of the National under-20 Dunlop Trophy tournament, and made it to the national teams. Balbir’s boys too went on to gain national and international glory, like former national captain Sarjit Singh.

There were dedicated officials too, apart from of course Suleiman who was the Father of Johor football, there were ENT specialist Dr Harjit Singh who held cricket together as an administrator, former Olympian ASP S.Sabapathy, Inspector Harbajhan Singh (Samurai), and MPJB president the late Datuk Ishak Yusof, in hockey. In their corners, they had the power to make things happen. And they did.

Yes, Johor grew from the boondogs of Malaysian sport, to a growing powerhouse. It was all very fulfilling. I met my wife in JB in 1981, got married to her in 1982, had my two boys there, and was settling down to life as a Johorean, and loving it. And then as fate would have it again, I got a letter in May 1986 asking me to report to the NST sports desk in KL in July. My second son, was just a month old, and I was preparing with some buddies in MBL then (now Guinness Anchor Berhad) to watch the Mexico 1986 World Cup in some of their outlets. I guess, his time I was being punished for enjoying my working life in JB. Yes, I was back on the road again. Only this time, I had to pack more than a suitcase. This time, it was a container load, driven by KC DAT. I was moving house, and getting back into battle stations.

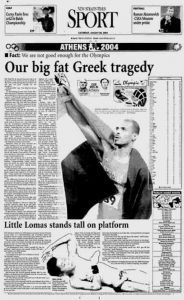

Yes, battle stations, for that’s what life for a competitive and combative sportswriter was in KL then. If you have been given a beat (sport) to handle, you can’t afford to lose a big story to the rival newspapers. You have to always be a few steps ahead of the rival media. Unless of course, you are that breed of beat reporters who didn’t mind getting your faces rubbed in the mud day in and day out by the opposition. Or those type of sportswriters who got their stories through the telephone. These days, they get their stories from websites.

No sir, not for me. I took great pride in my beat, and in my work. I would consider being beaten to a story in my beat, as an insult to my ability. And I loved to work with a team that was just as competitive and passionate. Which was why, I was looking forward to going back to KL with renewed enthusiasm, as Tony Francis had just taken over Timesport, Bill Tegjeu who was a very strong sub-editor, and the other half of the striking partnership, Fauzi, were all assembled like The Avengers, to beef up the NST sports pages. At the Malay Mail, our closest rivals, there was Johnson Fernandez and Tony Mariadass to contend with.

Even as the task at hand was still fun and exciting, my personal battles that were on account of my personality and my outspokenness, were very much ongoing. I remember in one sports desk meeting, Tony Francis, was complaining about stories from Fauzi and I, though well before deadline, but late by his standards. And he said, why we couldn’t file our stories before 7pm like the others.

I pounced back with: “Well, if you want us to get out stories on the telephone like the rest, and not be on the ground, then we can give you our stories even before 5 pm.”

Tony wasn’t amused, his face got red, and he slammed his cigarette pack and lighter on the table and said: ”Rokk, don’t rock the boat.” That same night, after he closed the pages, we were having a few beers in Bangsar. No one bore a grudge.

Then there was this time, when Bill Tegjeu had taken over with Tony moving up to Chief News Editor, and Fauzi moving to the London office as staff correspondent, the pressure of the back page lead stories seemed to rest solely and squarely on my shoulders. While the others weren’t as driven, it was entirely up to me to bring in the leads. And there were days when I couldn’t. And Bill used to chide me over that. And I asked him over a few beers once, why he saved the best punches for me. And he said: “Rokk, that’s because you can take it.”

It was then that it dawned on me, that this profession was actually defining the man I was then, and the man I am today. Yes, I could take the punches in my chin, and still remain standing, with plenty of fight left in me. Oh yes, there were more battles, but to me, it had become who I was, and who I am.

So I should really thank people like Kalimullah Hassan who was the group-editor-in chief in the 2000s, for suspending me for two weeks without pay because I didn’t run my stories past him. I was the sports editor then, and had 32 years of sportswriting experience under my belt, and here was a group editor — who was a businessman first and probably a journalist second – and who had no experience in sports, wanting to dictate terms. Sure, he was the boss, but he didn’t know enough about sports to dictate its policies.

This was the same guy, who in one management meeting, asked me why I had assigned two pages to school sports, during the school sports season. And when I explained to him that as a responsible newspaper, we needed to play our part in the development of sports in Malaysia, he said if that was the case, I should quit and join the then sports minister, Azalina Mohamed Said.

In this profession, you can’t be a businessman and a journalist at the same time. One will always be sacrificed, and almost all the time, it will be journalism. But in all fairness to Kali, he gave me my biggest pay rise ever. If there was one thing about him, he was colour blind. And the NST needed that, someone who didn’t appoint, promote, or judge you by your birthright, or your religion.

This job taught me about justice, about standing up for the truth and what is fair, and not for the individual. The individual in this equation, is of little consequence. Stand up for what is right first, and then for the individual who’s right. Not for the individual first, for then what is right, may be secondary.

I shared this philosophy with my children as they were growing up, so that their perspectives wouldn’t be skewed towards biasness towards individuals. Yes, journalism, specifically sportswriting, where we had more freedom to write, was a great teacher.

And I am thankful to all the battles in this journey, because they helped me find my strength. But when I look back at all those wonderful years, those painful experiences that I had overcome, I know now that God had always been there every step of the way, walking ahead of me.

If you have an interesting personal story of a sports personality with photographs and video, we would like to publish it on this site.

If you have an interesting personal story of a sports personality with photographs and video, we would like to publish it on this site.