By

By

Terence Netto: Sixty-five nations, Malaysia included, declined to send their athletes to the 1980 Moscow Olympics as a protest against the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Eighty other International Olympic Committee members chose to send their athletes. Whether the latter group made their decision to participate for sound or sorry reasons, history is likely to vindicate the premise that the Olympic Games should not be suborned by politics.

Malaysia’s decision to boycott the Moscow Olympics proved costly to our football team which qualified for the Olympics for only the second time in their history. To qualify the team once again beat South Korea in an Asian qualifying round, like their predecessors did, in order to make it to the 1972 Munich Games.

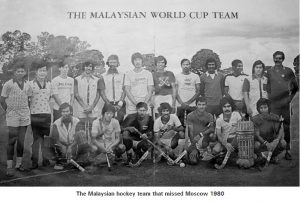

The national hockey team, too, qualified for Moscow, by dint of winning the bronze medal at the 1978 Bangkok Asian Games where they beat Japan in the match for third and fourth placings. The Malaysian hockey team had been, since the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, qualifying for the quadrennial summit of sport regularly, gaining a hitherto unattained eighth placing at the 1972 Munich Games and replicating that attainment at the following one in Montreal.

Pre-Independence Malaya (precursor of Malaysia) made its Olympic debut in hockey at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics where we finished 9th out of 12 teams. Centre half Mike Shepherdson was named to a World XI at the end of that debut which signalled that the small nation had in its casket a collection of hockey jewels. Though the country skipped the 1960 Rome Olympics due to financial reasons, a bronze medal at the 1962 Jakarta Asian Games levered the national team into the 1964 Tokyo Olympics.

The decision to boycott the 1980 Games interrupted a run of four Olympic appearances on the trot by the national hockey team. Although the Malaysian team returned to the Olympic arena at the 1984 Los Angeles Games, the no-show at Moscow was a blow to a slew of national players who had been inducted into the national team at the 1976 Olympics and would have relished the chance to embellish their claim to a kind of hockey immortality: successive appearances at the Olympics are regarded as an elitist badge of honour.

The Malaysian football team has not qualified for the Olympic Games since the Moscow boycott, a now nearly four-decade absence that is almost certain to last into the future. There is no saying that had the vintage the Malaysian players sported in 1980 been allowed an Olympic airing, the decline in international rankings the sport subsequently suffered may have been averted. It’s a hypothetical question, yet one of beguiling interest.

The government’s decision to boycott the Moscow Games was accepted by the sports establishment and sports press without demur. At that time, the sports press enjoyed more room that their political counterparts to criticise policies and acts of the executive. But the sports press did not make use of this latitude to critically scrutinise the decision to boycott.

Whether this stance of meek acquiescence stemmed from support for the decision to boycott or, what was more likely, insufficient consideration of what a no-show would mean to the affected athletes, the position has worn poorly with time. The press should have been less acquiescent.

Actually, there’s no place for politics in sports. Although it is very difficult to separate the sports sphere from the political one, this dichotomy has come to be regarded as a healthy necessity, like the separation of church and state in the political sphere.

Like water and oil, the two spheres cannot mingle and ought to be kept separate. On those sound grounds alone, the decision to boycott the Moscow Games ought to have been opposed.

Boycotting the Games meant that the top footballers, hockey players and other athletes in Malaysia who had reasonable hope of participating in the Olympics, were deprived of an all too rare chance of competing at what is considered the highest realm of sport where over a span of a fortnight the Games is a global cynosure.

No matter how one looks at it, the Olympics since its advent in 1896 is one of modernity’s great achievements, a two-week celebration of sporting ideals – Citius, Altius, Fortius (Faster, Higher, Stronger) – that however much they have been tainted in recent decades by corruptions such as drug use and bribery, retain their perjuring value.

That something like two score Malaysian top-notch sports performers of the late 1970s were deprived of the chance to gaining a semblance of Olympic lustre is regarded, in the perspective of the years gone by, as a callous decision, a snuffing out of human potential which by its nature has only a brief time span in which to flourish.

The sports press were remiss in not critiquing the decision and in reminding both government and the public that certain ideals must be preserved though the heavens fall.

If you have an interesting personal story of a sports personality with photographs and video, we would like to publish it on this site.

If you have an interesting personal story of a sports personality with photographs and video, we would like to publish it on this site.