By

By

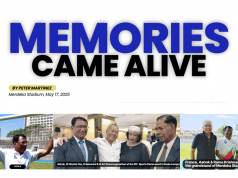

Terence Netto: Most Malaysian sports fans who lived through the period would be apt to argue that the era between 1966, when we earned an overachiever’s share of gold medals at the Asian Games, and 1980, when we qualified for, albeit did not go, to the Moscow Olympics, was the golden age of Malaysian sport.

Malaysia’s victory, though marred by volatile Indonesian fan behaviour, at the Thomas Cup in 1967; the soccer team’s unprecedented qualification for the 1972 Munich Olympics; and a hitherto unattained fourth place at the 1975 World Cup of hockey, were a triad of achievements which fortify the claim that the 1966-80 period was the anni mirabilis of Malaysian sport.

The accuracy of this description is reinforced once we factor in the popular satisfaction felt in Dr Mani Jegathesan being declared “Asia’s fastest man” at the 1966 Bangkok Asiad; the exhilaration of shuttler Tan Aik Huang’s winning the All-England singles title in 1966, and the doubles combo of Tan Yee Khan and Ng Boon Bee thrillingly grabbing practically every title in sight in the mid-1960s, for a grand Malaysian haul of coveted laurels in that halcyon era.

Though it was a fleeting moment of glory, Mokhtar Dahari’s brilliant goal from 40 metres out against the England B football team in May 1978, his shot dipping in flight over out-of-position keeper Joe Corrigan, underscored the Malaysian potential for tantalising glimpses of world class potential, if, alas, largely unfulfilled.

Adding piquancy to the flavour of those early achievements was the unofficial declaration of Vijayanathan Gulasingam in the 1975 World Cup — which Malaysia staged in a rousing exposition of the sport’s aesthetic values – as the best hockey umpire in the world.

His awarding a disputed goal to India in a rapturous final match contested by Pakistan displayed the discerning, delicate touch of a surgeon separating Siamese twins joined at the head.  This last bit of arcana paves the way for a discussion of sports administration values the country was gifted to enjoy, simply from having three of the most skilled secretaries of national sports bodies who were also widely perceived as just about the best of the kind in the world.

This last bit of arcana paves the way for a discussion of sports administration values the country was gifted to enjoy, simply from having three of the most skilled secretaries of national sports bodies who were also widely perceived as just about the best of the kind in the world.

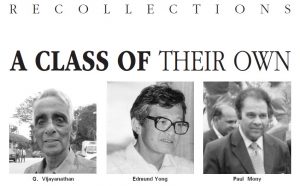

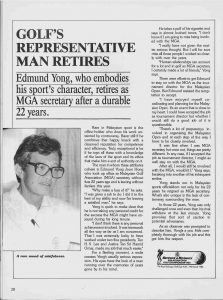

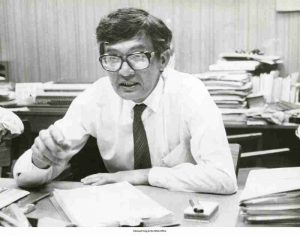

The three were Viji, as he was popularly called, Edmund Yong Joon Hong in golf, and Paul Mony Samuel in football.

Near contemporaries Viji and Edmund were in harness in the Malaysian Hockey Federation and Malaysian Golf Association respectively over about the same span of time, from the 1960s through to the early 1980s.

Paul Mony was appointed to the general secretary’s post in the Football Association of Malaysia in 1984 when our position in FIFA’s rankings had begun their slide into what seems like lasting mediocrity.

As that slippage took effect, international observers were puzzled as to why Malaysian football was sliding while the administrative mettle of its general secretary was regarded as world class. If this discrepancy was the subject of discussion among international observers, among local sportswriters it became the topic of handwringing commiseration.

To be sure, administrative skills and on-field sports performance belong to a different order of things. But just as Paul Mony did not appear like an apparition out of thin air, for that matter neither Viji nor Edmund Yong, but instead sprung out of the whole cloth of Malaysian sport, the 1950s’ subcultures which produced all three standouts were already waning when this trio displayed their vintage in the national bodies they steered and for the regional and continental bodies, to which they were appointed, because of their merits.  The chief features of the subcultures were an education system that had English as the medium of instruction, schooling that emphasised academic attainments in tandem with extracurricular distinction, and propped up by an ethos that did not lose sight of the fact that certain pursuits must be done for the intrinsic satisfaction they afford more than the extrinsic rewards that could be gained.

The chief features of the subcultures were an education system that had English as the medium of instruction, schooling that emphasised academic attainments in tandem with extracurricular distinction, and propped up by an ethos that did not lose sight of the fact that certain pursuits must be done for the intrinsic satisfaction they afford more than the extrinsic rewards that could be gained.

All these features began their descent into oblivion from our national milieu as this trio of top qualify administrators reached the heights of their capabilities. A social engineering process was afoot in the country that had negative consequences on all aspects of national endeavour. Against this backdrop of decline, this trio stood exceptionally apart. Edmund Yong was held to be capable of refereeing the Masters competition at Augusta National, Viji would have been a credit to the FIH, the French initials of the world body for hockey, and Paul Money could have administered FIFA minus the dross that has floated in Joseph Blatter’s slipstream.  Incidentally, long-time FIFA general secretary Sepp Blatter, on an evaluation visit to FAM in the early 1990s, pronounced the national body as one of the best run in the world. Paul was then the general secretary.

Incidentally, long-time FIFA general secretary Sepp Blatter, on an evaluation visit to FAM in the early 1990s, pronounced the national body as one of the best run in the world. Paul was then the general secretary.

When he left the FAM post in mid-2000, the national body had RM5 million in cash deposits and fixed assets of RM100 million. Upon assumption of the post in 1984, the corresponding figures were RM500,000 and RM5 million. It was caretaking of the highest probity.

In a 32-year career (1975-2007) as a sportswriter, I consider myself gifted to have observed all three Malaysians in their administrative prime. Watching them at work was a delight in itself. But more than delight, it was an education.

I was too young to realise its meaning even as I witnessed it, but it was an education into what I eventually understood as the profound truth of what the writer E.M. Forster, of Passage to India fame, opined about the need for democracy in human affairs.

He said that all government is about force and that democratic government is the least destructive of such force because its processes draw out and camouflage this force. He said the good of this deliberative process lay in how it enables the real work of man to be done and the real life of man to be lived.

Watching Viji, Edmund and Paul, I saw real work being done and how that enhanced the lives set free to be lived. Probably because he had a life outside of his passions, which were sports administration and hockey umpiring, Viji has endured the longest of the three, alive and still vital, at 86 years, as I write.

Edmund died of cancer in 1997 close on 62 years and Paul succumbed to Parkinson’s disease in 2016 when he neared 72. Of the trio, I most benefited from watching Paul Mony because of what I felt was the breadth of his vision, depth of his understanding, and, more importantly, the generosity of his spirit.

Our lives are blinks of duration but when they possess what Viji exuded, Edmund epitomised and Paul embodied, they can be tiny diamonds in the cosmic sands.

If you have an interesting personal story of a sports personality with photographs and video, we would like to publish it on this site.

If you have an interesting personal story of a sports personality with photographs and video, we would like to publish it on this site.