By

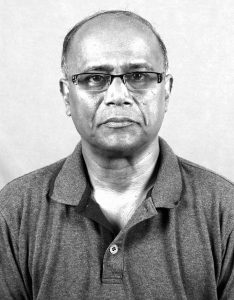

Terence Netto: In 1973, when I began as a cadet reporter in New Straits Times, I was made quickly aware that Dato’ Harun Idris’s magnetism as a sports leader was a byword among senior sportswriters. He was a charismatic politician whose love of sports resembled Tunku Abdul Rahman’s and he shared the founding prime minister’s confidence that the medium would unite the diverse peoples of the country. Harun had studied at Victoria Institution, renowned spawning grounds of the societally eminent, and after graduating in the law from the Inns of Court in London in the early 1950s, became legal adviser to the Selangor government later that decade. He was president of the Selangor Football Association.

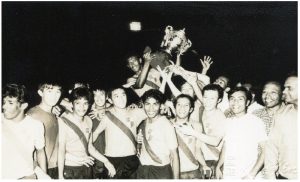

As manager of the highly successful Selangor state team in the national league, Harun rose in the ranks of the Football Association of Malaysia to become vice president by the mid-1960s. Simultaneously, he was manager of the national football team, a tenancy that would be marked by increasing success as Malaysia won the Merdeka Tournament in 1968, after a title-drought of several years, and qualified for the 1972 Munich Olympics, the first time we ever did.

In tandem with his sports-leadership career, Harun’s political ascendancy gathered pace. It accelerated after he became leader of the increasingly powerful youth wing of his party, Umno, which by the early 1970s had become the dominant force on the political scene.

Umno Youth became assertive. The social engineering process afoot in the country gave it newfangled prominence. Under a leader whose public profile was rising on the national sports scene and whose political eminence was embellished by his state’s heft in the national economic scenario, Harun, by the mid-1970s, had become prime ministerial material.

Local sports leaders and organisers drooled in anticipation of a premiership by someone who they were sure that, because of his knowledge of sport and ability to collate advice from experts, would lever the country to prominence as a contender for honours in regional, continental and global arenas.

Football was the country’s most popular sport. The qualification of the national team to the 1972 Munich Olympics was regarded as a sign of its potential for entry into the higher echelons of the international game.

Harun was the manager of the team that qualified for the Munich Olympics in 1972. At that point, he had been manager of the national team for several years, with the qualification to Munich the high point of his tenure. Harun was widely regarded as a players’ manager, in the sense that he knew how his players felt and he made decisions in their and the team’s best interests.

A case in point was the exclusion of striker Syed Ahmad from the team bound for the Munich Olympics. A prolific goalscorer who starred in the qualifying round held in Seoul a year before the Olympics, Syed Ahmad had problems with discipline that were particularly serious during a tour of Europe the squad underwent in the lead-up to the Olympics. Harun, a stickler for discipline, backed coach Jalil Che Din’s decision to drop the recalcitrant striker from the Olympics-bound squad. It seemed that a player’s formidable on-field standing would not be allowed to outweigh what was considered to be serious defects of discipline. Although Harun was mainly a football-focused sports leader, he was keen on other disciplines, especially when these threw up on the national stage formidable exponents from among Selangorians. As chief minister of the state, he was interested in how sports performers born in the state fared in national competitions.

He was known to support these performers when they were in need of aid he could procure for them as the CEO of the state.

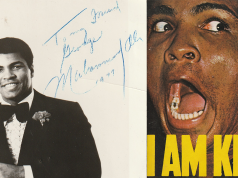

1975 was a year of great moment in Malaysian sport. In March, the Malaysian Hockey Federation staged a highly successful World Cup that premiered to rousing crowds and scintillating play. In June, Kuala Lumpur also saw the staging of a heavyweight boxing match between the legendary Muhammad Ali and Britain’s Joe Bugner. For a brief period between March and June, it seemed that Kuala Lumpur was the capital of momentous happenings in world sport.

No doubt, it was a blue riband year. But this auspicious year came with an ominous lining for Harun. He was instrumental in getting the Ali-Bugner match staged in Kuala Lumpur, with matters to do with the organization of the event handled by a newly set-up company called Tinju Dunia. The company would become the subject of police investigations that led to Harun being indicted for corruption in November 1975.

By March the following year, Harun was found guilty and sentenced to prison. The case’s outome presaged the eclipse of a politician-cum-sports leader that many felt was best equipped for leading the country at that stage of its evolution.

In the perspective of the decades gone by, the corruption case against Harun came to be regarded as a political prosecution. His evanescence from the national political and sports scene also came to be viewed as deletrious to our prospects in both arenas for reason of a perceived ability to strenghten the best purposes and suppress the worst instincts of a motley democracy.

By the time of Harun Idris’s death at the age of 78 in September 2003, his eclipse and eventual demise was viewed as tragic, in some sports circles at least. Tragedy is amputation: the strands of memory run to the what-might-have-been had he not encountered the fate he did.

If you have an interesting personal story of a sports personality with photographs and video, we would like to publish it on this site.

If you have an interesting personal story of a sports personality with photographs and video, we would like to publish it on this site.